The Philippines

Overview

The Philippines, an archipelagic nation with over 114 million people, is one of Southeast Asia's most populous countries. Characterized by a young and growing population, the country is experiencing rapid urbanization and expanding consumer markets. In 2024, the Philippines achieved a robust GDP growth rate of 5.6%, positioning it as one of the fastest-growing economies in the East Asia and Pacific region. This economic momentum is expected to elevate the country from lower-middle- to upper-middle-income status by 2026, supported by structural reforms and recovery efforts (World Bank, 2025).

Despite notable improvements in poverty reduction and child health outcomes, the Philippines continues to grapple with a persistent double burden of malnutrition affecting multiple age groups. According to the 2023 National Nutrition Survey (NNS) by the Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI) (2025a), malnutrition in the Philippines persists across age groups. Among children under five, 23.6% were stunted, indicating chronic undernutrition. Stunting was also observed in 17.9% of school-aged children and 20.7% of adolescents. Simultaneously, overnutrition is rising, with 12.9% of school-aged children, 5.8% of adolescents, and a combined 57.1% of adults aged 20-59 years classified as overweight or obese. This situation is contributing to an increasing burden of diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) (2025), out of a total of 548,821 deaths recorded from January to November 2024, the leading causes were ischemic heart diseases (19.3%), neoplasms or cancers (11.1%), cerebrovascular diseases (9.8%), diabetes mellitus (6.3%), and hypertensive diseases (5.4%). These five conditions are classified as major NCDs and together account for more than half of all recorded deaths in the country. They are closely linked to modifiable lifestyle and dietary risk factors such as unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. The co-existence of undernutrition and a rising burden of NCDs highlights the double burden of malnutrition and underscores the urgency of integrated public health strategies that address both nutrient inadequacy and the increasing prevalence of chronic diet-related diseases.

Food insecurity remains a critical factor that further compounds the country's nutrition challenges. The 2021 ENNS (DOST FNRI, 2024) showed that approximately 33.4% of Filipino households experienced moderate to severe food insecurity, with higher prevalence in rural and low-income populations. More recently, a national survey conducted by the Social Weather Stations (2025), 20.0% of Filipino families experienced involuntary hunger in April 2025, defined as going without food at least once in the past three months. This represents a decline from 27.2% recorded in March 2025. Key drivers include food price inflation, climate-related agricultural disruptions, and reliance on rice imports. Dietary quality in food insecure households is poor. The 2023 National Nutrition Survey (NNS) Food Consumption Survey (DOST FNRI, 2025b) reported that rice and rice-based products account for around 50% of the average Filipino's energy intake, far exceeding recommended levels for a balanced diet. While vegetables (14.5%) and fish (10.8%) are also commonly consumed, the intake of other nutrient-rich foods such as fruits, legumes, root crops, and tubers remains low. This dietary imbalance contributes to the country's persistent double burden of malnutrition.

Recent shifts in the Philippine food environment have significantly influenced dietary behaviors and nutrition outcomes. The rapid growth of supermarkets and convenience stores, especially in urban areas, has increased the availability of processed and ultra-processed foods, often high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats. The Philippine food retail market experienced an 8% growth in 2023 despite inflationary pressures, fueled by expanding modern retail stores and rising incomes from overseas workers and increased employment (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2024). This retail expansion, along with omnichannel marketing strategies and greater availability of imported and processed foods, has significantly altered the food environment, especially in urban areas. The grocery retail market was valued at US$59 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach US$82 billion by 2028 (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, 2024). While traditional sari-sari stores still account for the majority of sales, modern supermarkets, hypermarkets, and e-commerce platforms are rapidly expanding. In 2023, Filipino consumers spent US$632 million on food and beverage products online, highlighting the growing role of digital channels in food access and marketing (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, 2024). These developments have contributed to changing consumption patterns that favor unhealthy foods, exacerbating the rise in overweight, obesity, and diet-related NCDs in the country.

Key Food and Nutrition Indicators

The 2023 National Nutrition Survey (NNS), conducted by the Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI) (2025a, 2025b), provides the most up-to-date empirical data on the nutritional and health status of Filipinos. As a nationally representative survey, the 2023 NNS serves as a vital resource for informing policy and program decisions at both national and regional levels. It offers a comprehensive picture of the country's key nutrition challenges, including the prevalence of undernutrition, overweight, and stunting, alongside food insecurity, urban-rural disparities, and dietary behaviors such as fruit and vegetable consumption.

Based on the 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025a), the nutritional status of Filipinos across age groups reflects a clear and persistent double burden of malnutrition. Undernutrition remains a major concern among preschool-aged children, with underweight, stunting, and wasting still widely observed. At the same time, the presence of overweight in this age group indicates the early onset of overnutrition. Among school-aged children, undernutrition persists and, in some cases, becomes more pronounced, even as the prevalence of overweight and obesity continues to rise. The adolescent population shows similar patterns, with both chronic undernutrition and excess weight conditions appearing side by side. In adulthood, the nutritional profile shifts more heavily toward overnutrition, as overweight and obesity affect a growing share of the population. This trend continues into older age, where excess weight remains a dominant concern. These patterns underscore a complex nutrition landscape in the Philippines, where efforts must simultaneously address longstanding deficits in growth and the rapidly increasing rates of diet-related chronic conditions.

In the Philippines, the consumption of fruits and vegetables remains consistently below optimal levels across all age groups, as highlighted by national dietary data. The 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025b) shows that vegetables comprise only 14.5% of the average Filipino household's daily food intake, while fruit consumption remains notably low. Detailed data from the 2021 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS) (DOST FNRI, 2024a) further reveal that infants and preschool children (6 months to 5 years old) consume only 11 grams of vegetables (4.1%) and 7 grams of fruits (2.7%) daily. Among school-age children (6-12 years), vegetable intake rises slightly to 25 grams (5.9%) and fruit consumption to 12 grams (2.7%). Adolescents (13-18 years) consume 39 grams of vegetables (7.0%) and just 12 grams of fruits (2.1%), while adults (19-59 years) average 58 grams of vegetables (9.5%) and 17 grams of fruits (2.8%). Older persons (60 years and above) show the highest relative intake with 57 grams of vegetables (11.1%) and 22 grams of fruits (4.3%). Despite some increase with age, overall fruit and vegetable consumption remains far below recommended levels, underscoring a critical area for dietary improvement to support better nutrition and reduce the risk of noncommunicable diseases in the Filipino population.

Food insecurity continues to be a major concern in the Philippines. Based on the 2021 ENNS (DOST FNRI, 2024b), about one-third (33.4%) of Filipino households faced moderate or severe food insecurity, with 2.0% experiencing severe food insecurity. Many families reported worrying about not having enough food (68.5%), eating only a limited variety of foods (43.8%), and being unable to consume healthy and nutritious food (35.4%). Other reported experiences include eating less than needed (32.6%), running out of food (25.3%), skipping meals (20.7%), going hungry but not eating (10.9%), and not eating for a whole day (2.0%). Larger households and those in rural areas were more likely to experience food insecurity, although differences were not statistically significant. The 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025a) showed a slight decrease, with 31.4% of households experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity. The prevalence was higher in rural areas (35.3%) than in urban areas (27.8%), and among households with more than five members (37.1%) compared to those with five or fewer (29.5%). These trends highlight the ongoing challenge of ensuring food security, especially for vulnerable groups.

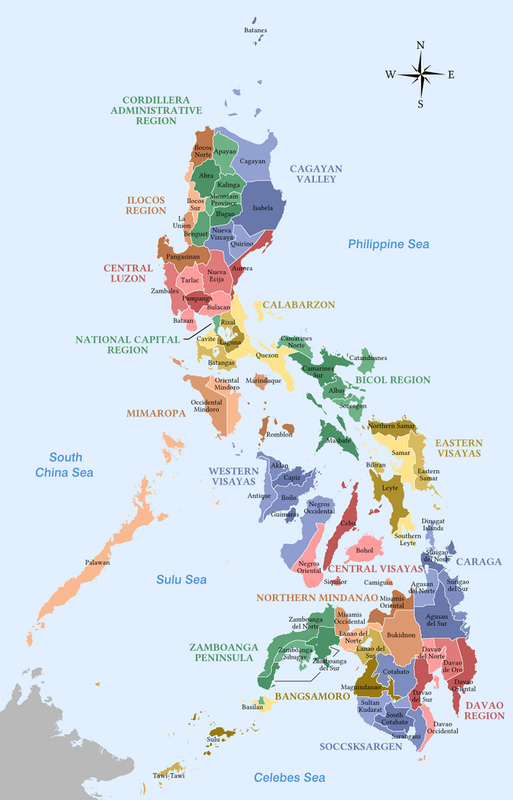

Significant differences persist between urban and rural areas in food and nutrition indicators in the Philippines. Rural households continue to experience higher rates of undernutrition, stunting, and food insecurity compared to urban counterparts. The prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity was higher in rural areas (34.5% in 2021, rising to 35.3% in 2023) than in urban areas (27.8% in 2023) (DOST FNRI, 2024b, 2025a). Stunting and underweight are also more common among rural children under five. In contrast, overweight and obesity have become more prominent in urban populations, especially among adolescents and adults, with the 2021 ENNS showing higher rates of overweight and obesity in cities (DOST FNRI, 2024b). These trends highlight the need for targeted policies to address both persistent undernutrition in rural areas and rising overweight in urban settings. Without decisive action to address these dual burdens, health inequalities between urban and rural populations are likely to widen. More rigorous monitoring and evaluation are needed to ensure that future programs effectively respond to the changing nutrition landscape.

The Philippines' nutrition strategy centers on its Dietary Guidelines and the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN) 2023-2028 (see National Nutrition Council, 2023), which aim to eliminate all forms of malnutrition across all age groups. The guidelines encourage healthy diets, optimal breastfeeding, and limited intake of sugar, salt, and fat, while PPAN sets concrete outcome targets. For pregnant and lactating women, the plan targets annual reductions in nutritional risk and anemia, improved iodine status, and lower vitamin A deficiency rates. For children under five, the goals include cutting low birth weight and stunting, reducing wasting to below 5% by 2025, and halving stunting numbers by 2030, as well as raising exclusive breastfeeding rates to 50% and boosting dietary diversity. School-aged children and adolescents are targeted with reductions in wasting and overweight, maintenance of adequate iodine, and a halt to rising obesity rates. For adults and older persons, PPAN seeks to reduce overweight, obesity, and chronic energy deficiency. At the household level, the plan aims to cut moderate and severe food insecurity by 5.1% per year, increase recommended energy intake, and achieve universal salt iodization by 2028. These guidelines and targets are designed to address the country's dual burden of undernutrition and overweight, requiring strong multisectoral commitment and regular progress monitoring to achieve better health for all Filipinos.

Policy Landscape and Governance

The governance of food and nutrition in the Philippines relies on a network of key institutions working together to address the country's nutrition challenges. The National Nutrition Council (NNC), which operates under the Department of Health, leads coordination for policy direction and program implementation. Other major agencies such as the Department of Agriculture, Department of Social Welfare and Development, Department of Science and Technology, and Department of Education all contribute to planning, delivering, and overseeing nutrition and food security initiatives. Coordination among these agencies, as well as between national and local governments, is crucial but often difficult to achieve in practice, which can limit the effectiveness of well-designed strategies.

On the strategic level, national frameworks such as the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN) (see National Nutrition Council, 2023), the National Food Policy, and the Philippine Development Plan (see the Philippine Development Plan 2023-2008) provide overall direction and set priorities for addressing malnutrition and improving food environments. These frameworks are reinforced by sectoral policies in agriculture, health, and social protection, all reflecting a strong national commitment to nutrition and food security. However, the impact of these policies can be undermined by fragmented implementation and uneven allocation of resources, especially at the local level where capacity and funding may be limited.

In the area of regulatory policies, food labeling is governed by the Food Safety Act of 2013 (Republic Act No. 10611), the Food and Drug Administration Act, and the Consumer Act of the Philippines. These laws require nutrition facts and ingredient lists on packaged foods, and Department of Health Administrative Orders further clarify labeling requirements. Despite these legal provisions, monitoring and enforcement remain inconsistent due to agency capacity constraints. Many ultra-processed or imported foods do not consistently comply with labeling standards, and the lack of a mandatory front-of-pack warning system for foods high in sugar, salt, or fat limits consumers' ability to make healthy choices and leaves them vulnerable to misleading claims.

Food marketing regulations, particularly those protecting children, remain an area of concern. The Consumer Act and Executive Order 51 (Milk Code) impose some restrictions on deceptive advertising and the promotion of breastmilk substitutes. Still, there is no comprehensive national law to limit the marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children. Administrative orders, such as DOH AO No. 2021-0039, help address specific harmful ingredients like trans-fatty acids, but digital and television marketing for unhealthy foods continues to reach young audiences with little restriction. Some local ordinances, including the Quezon City Anti-Junk Food and Sugary Drinks Ordinance, show the potential of local action, yet these are not widespread and lack national enforcement.

Healthy retail incentives are gradually being promoted through policies such as the High-Value Crops Development Act of 1995 and various local government initiatives that support the availability and sale of fruits, vegetables, and nutritious foods in public markets. However, the absence of a unified national law and the reliance on local leadership mean that effective programs are limited in their scale and sustainability. Many of these initiatives remain short-lived, and the lack of consistent funding or national coordination hinders their long-term impact.

Public procurement policies, such as DepEd Order No. 13, s. 2017 and Healthy Food Procurement Acts, establish nutrition standards for food served in schools and government institutions, with the goal of ensuring healthier food options for vulnerable populations. The TRAIN Law, which taxes sugar-sweetened beverages, is another policy tool intended to discourage the purchase of unhealthy foods in public settings. Nonetheless, the actual supply and procurement of healthy foods often face challenges related to budget limitations and weak monitoring. For meaningful progress, it is essential to embed strong nutrition standards within procurement systems and to ensure robust compliance and accountability mechanisms across all levels of government.

Food Environment Features

Retail trends in the Philippine food environment are shaped by a complex interplay between traditional markets, modern retail, and the rapid growth of online delivery. Traditional outlets such as sari-sari stores and wet markets account for nearly 65% of all grocery retail sales according to industry reports (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, 2024). The 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025b) confirms that almost all Filipino households, whether in urban or rural areas, depend on these outlets for daily food needs because they are affordable and accessible.

Modern supermarkets and hypermarkets, including Robinsons, SM, and Puregold, are expanding in urban centers. However, their higher prices and limited reach mean they remain a secondary choice for most families. Convenience stores have also gained popularity, generating US$2 billion in sales in 2023 and offering ready-to-eat meals with 24-hour accessibility. E-commerce and online delivery are growing, with Filipinos spending US$632 million online for food and beverages, but these platforms are mainly accessed by urban and higher-income consumers (New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, 2024). With many families relying on small-quantity packaging and frequent shopping, traditional markets are expected to remain the cornerstone of food access in the Philippines even as modern and online channels continue to expand.

Marketing plays a powerful role in shaping the food environment in the Philippines, influencing what people see, desire, and ultimately choose to eat. Across the country, food and beverage companies use a wide range of advertising strategies, from billboards and television commercials to in-store promotions and digital campaigns, to drive demand for their products. The rise of social media and online platforms has made these marketing efforts more pervasive and targeted than ever, allowing brands to reach consumers of all ages directly in their homes and on their phones. This marketing environment is particularly concerning when it comes to children and youth, who are especially vulnerable to persuasive advertising.

According to a 2023 UNICEF analysis of 1,035 marketing posts and videos on food brand social media pages in the Philippines, over 99% were not suitable for marketing to children according to World Health Organization regional criteria (Tatlow-Golden, 2021). Nevertheless, 72% of the posts appealed to children and 84% to adolescents, often using themes of fun, taste, enjoyment, family relationships, and health. These advertisements frequently featured brand characters, cartoons, bright colors, interactive games, and family bonding moments, with one in five posts showcasing Filipino celebrities endorsing products high in sugar, salt, or fat. This approach resonates deeply with Filipino culture and effectively fosters unhealthy food preferences and consumption among children and adolescents, increasing their risk of nutrition-related health problems.

The influence of marketing on Filipino food choices is compounded by persistent challenges in accessing affordable, healthy foods. According to the 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025b), rice accounts for 35.7% of the average household's daily food intake and provides 58% of total energy, while vegetables and fish make up 14.5% and 10.8% respectively. Despite some improvement in nutrient adequacy since 2018-2019, the intake of fruits, legumes, and other nutrient-rich foods remains low, especially among poorer families who rely more heavily on rice as their staple. Rising food prices, limited food infrastructure, and persistent poverty continue to restrict access to a diverse and nutritious diet. In response, the government has implemented programs such as the High Value Crops Development Program, nutrition standards for schools and public institutions, and local initiatives like urban gardening and farm-to-school programs to help increase the supply and accessibility of healthy foods. Despite these interventions, many families still face significant barriers to achieving a healthy diet, highlighting the urgent need for more effective, coordinated strategies to make nutritious and affordable food accessible to all Filipinos.

Beyond affordability and availability, gender and equity considerations further shape food access across the Philippines. Women, particularly mothers, continue to play a central role in food selection, budgeting, and meal preparation in most households. Recent survey data show that both male- and female-headed households are affected by moderate to severe food insecurity, with a slightly higher prevalence among male-headed households. The 2021 ENNS (DOST FNRI, 2024b) reported that 34.0% of male-headed households experienced moderate to severe food insecurity compared to 31.4% of female-headed households, a pattern that remained in the 2023 NNS (DOST FNRI, 2025a), where 32.4% of male-headed households and 29.0% of female-headed households reported similar levels of food insecurity. Broader socioeconomic inequalities also limit food access among the poorest families, rural communities, and marginalized groups such as indigenous peoples, who tend to rely more on basic staples and have less access to diverse, nutrient-rich diets. In addition, micronutrient deficiencies continue to disproportionately affect women and girls, with significant rates of anemia among pregnant women and women of reproductive age. Geographic disparities compound these challenges, as urban households generally have better access to a wider variety of foods, while rural and remote communities face more limited choices and greater risks of undernutrition and food insecurity (DOST FNRI, 2024b, 2025a). These patterns highlight the urgent need for nutrition policies and interventions that address both gender- and equity-related barriers, ensuring that all Filipinos, especially women, children, and vulnerable populations, can access affordable and nutritious food.

References

- Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI). (2024a). Philippine nutrition facts and figures: 2021 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS): Food consumption survey. DOST FNRI. https://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/uploads/2021%20ENNS%20FandF%20Food%20Consumption%20Survey.pdf

- Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI). (2024b). Philippine nutrition facts and figures: 2021 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS). DOST FNRI. https://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/uploads/2021%20ENNS%20Facts%20and%20Figures.pdf

- Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI). (2025a). Halfway point to 2030: Key findings of the 2023 National Nutrition Survey. DOST FNRI. https://enutrition.fnri.dost.gov.ph/infographics.php?year=2023

- Department of Science and Technology, Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST FNRI). (2025b). DOST-FNRI unveils 2023 Filipinos state of health and nutrition [Press release]. https://www.dost.gov.ph/knowledge-resources/news/86-2025-news/4067-dost-fnri-unveils-2023-filipinos-state-of-health-and-nutrition.html

- National Nutrition Council. (2023). Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN) 2023-2028. https://nnc.gov.ph/plans-and-programs/philippine-plan-of-action-for-nutrition-ppan/

- New Zealand Trade and Enterprise. (2024). Selling food and beverage to the Philippines' grocery retail market. https://my.nzte.govt.nz/article/the-philippines-food-and-beverage-retail-sector

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). (2025, June 26). 2024 causes of death in the Philippines (Provisional as of 30 April 2025) [Press release]. https://psa.gov.ph/content/2024-causes-death-philippines-provisional-30-april-2025

- Social Weather Stations. (2025, June 27). First quarter 2025 social weather survey: Hunger at 20.0% by end of April 2025 [Press release]. https://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/?artcsyscode=ART-20250627174857

- Tatlow-Golden, M. (2021). Unhealthy digital food marketing to children in the Philippines. UNICEF Philippines Country Office. https://www.unicef.org/philippines/reports/unhealthy-food-marketing-children-philippines

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2024, October 3). Philippines: Retail foods annual (GAIN Report No. RP2024-0032).

- World Bank. (2025). The World Bank in the Philippines: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/philippines/overview